Introduction

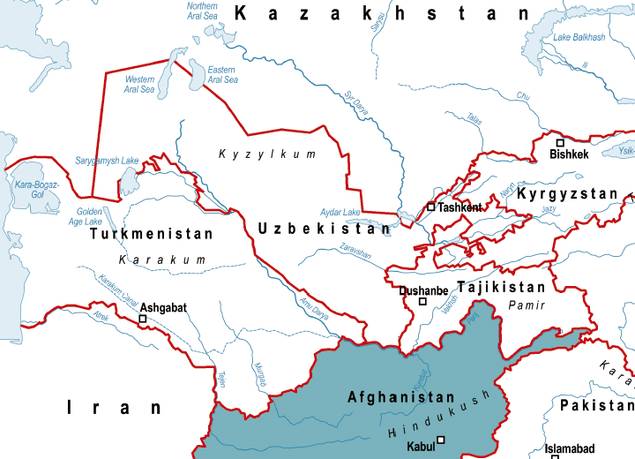

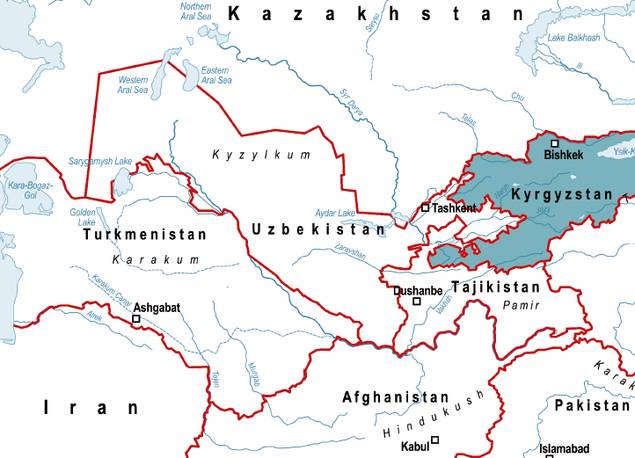

Central Asia is a huge landmass situated between the world’s largest inland water body, the Caspian Sea, and the mountain ranges of the Tian Shan, Pamirs and the Hindukush. For centuries, caravans travelled along the famed Silk Road-actually there were many-to connect the civilizations of Europe and Asia, crossing deserts, grassy steppes and mountain ranges. Powerful Khans built cities and centres of Islamic scholarship and developed sophisticated irrigation systems to compensate for the region’s low rainfall. These systems focused primarily on the two main rivers that carry the snowmelt of the Central Asian mountain ranges west to the Aral Sea: the Amu Darya (darya means river in Persian), which was known by the ancient Greeks as the Oxus, and the Syr Darya (the Jaxartes, or Pearl River, to the Greeks). Before 1991 and the break-up of the Soviet Union, both rivers ran mostly inside the USSR, along with a small part of Afghanistan. Today, sharing the water has become much more complicated because the rivers cross the territory of six independent states: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, along with Afghanistan.

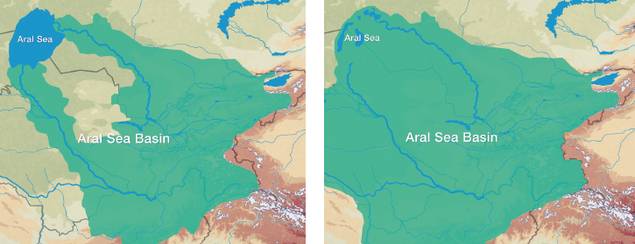

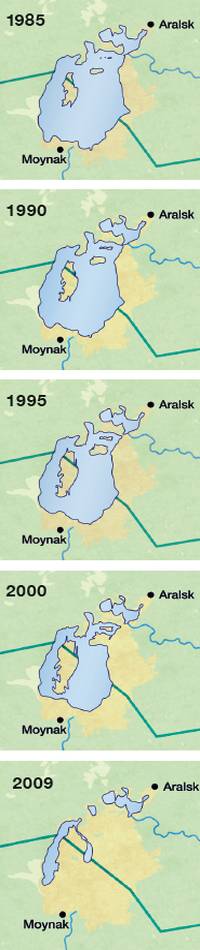

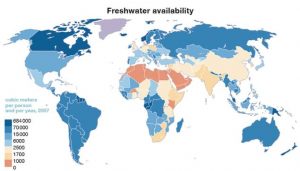

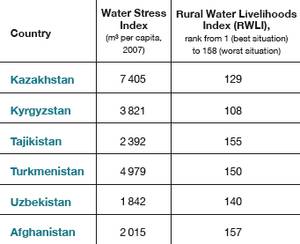

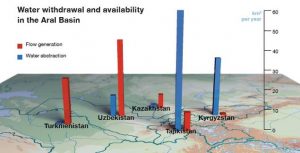

Water is unevenly distributed in Central Asia. Most of the renewable surface water is formed in the mountain regions of Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Afghanistan, while most of it is used in the downstream countries of Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Starting in the 1960s, the Soviet authorities began a massive irrigation expansion that drew water from both rivers to increase cotton production. The result was that much less water reached the Aral Sea, then the world’s fourth-largest inland lake, than was required to compensate for evaporation. The sea is now a tenth of its size half a century ago.

With the disintegration of the Soviet Union, the five newly independent states faced the challenge of cooperating with each other and with Afghanistan to determine how to share the water and also how to address the Aral Sea desiccation.

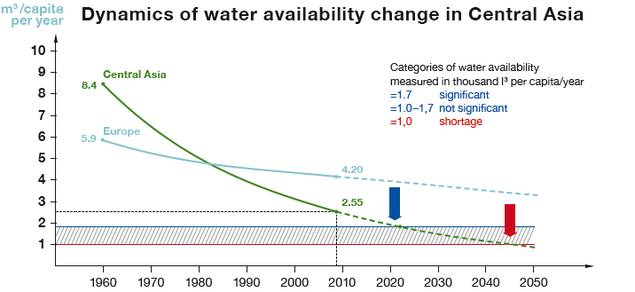

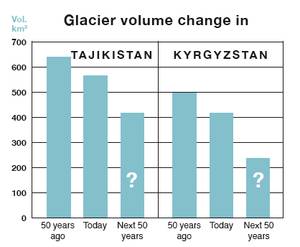

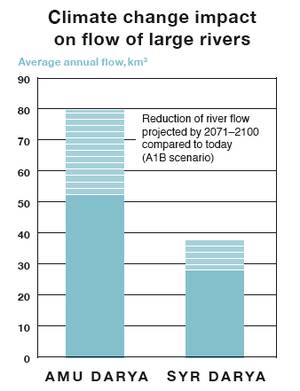

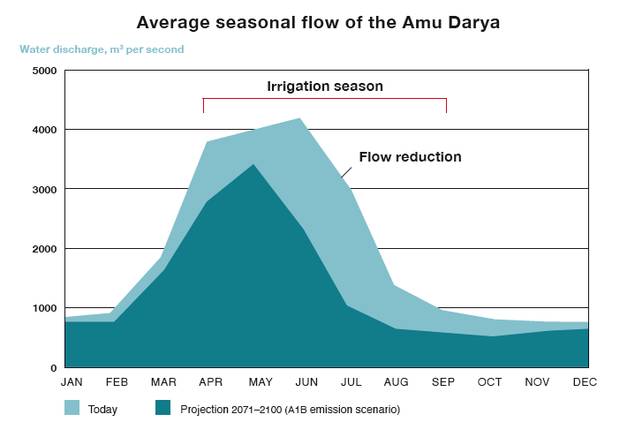

They had to learn how to do this against a backdrop of growing populations, institutional upheavals and climate change. Global warming has already caused glaciers feeding both rivers to melt, temporarily increasing flow but promising long-term decreases. At the same time, warmer temperatures will mean increasing losses due to evaporation, both in irrigation and in the reservoirs.

Given these challenges, in the early 1990s many experts expressed concerns that future shortages could heighten tensions among the six Central Asian states. Instead, what emerged over the last 20 years was a process of building up and institutionalising regional cooperation on water management. This book will give an overview of the achievements so far, the remaining weaknesses and challenges, and of future prospects.

Water Management in Central Asia:

The Legacies of the Past

The five former Soviet states of the Aral Sea Basin, thus excluding Afghanistan, share a common history under Russian and Soviet rule with tremendous effects on water usage and water management. This common past will be described in this chapter.

Historical patterns of water usage and water management

Central Asia has a long history of irrigation agriculture. Over the course of the centuries, complex and sophisticated systems of water management evolved in order to compensate for low rainfall. The prosperity of the Arab period in the 7th century came in part from the construction of extensive irrigation systems in the sedentary areas. There, control over where water went was centralized, while its end use was the responsibility of local officials. The Khan acted as a kind of trustee of water in the name of Allah. Farmers paid taxes for water usage and were obligated to participate in necessary maintenance work. So-called mirabi-water masters-were responsible for secondary canals and aryk aksakaly (literally: canal elders) for small canals. The highest position was the mirab bashi, who was part of the government and responsible for water allocation. The mirab was elected and received a payment in kind from the users depending on how satisfied they were with his work. These were very prestigious positions. Besides the mirab, another informal water governance institution was the hashar or ashar, a system of collective voluntary work by community members. It was part of a broad system of reciprocities at the village and neighbourhood level. Hashar was used for construction, rehabilitation and maintenance of small-scale canals.

In the 1860s, Central Asia-then called Turkestan-fell under the control of Tsarist Russia. Its agricultural policy fostered the expansion of cotton production and of the irrigation systems the water-intensive crop requires. In most cases, the former management system was maintained, but with a key change: instead of being paid by, and accountable to, the water users, the mirab and aryk aksakal became employees of the Russian Empire. This meant that they had less incentive to maximize efficiency. To make things worse, irrigation officials without local knowledge were sent in just as the competition for water intensified with the cotton expansion. As a consequence, traditional institutions of water management were weakened while no effective new control mechanisms were introduced; corruption and unapproved water withdrawal spread.[Bichsel 2009, O’Hara 2000, Thurman 2002.]

Water usage and water management in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union continued to realize many of the ambitious plans of the Tsarist period. It financed and constructed more large-scale irrigation networks. Apart from the economic objective of establishing the Soviet Union on the world cotton market, agricultural policies in Central Asia also aimed to develop this poorest region of the Soviet Union. New water infrastructure was critical to supplying the rapidly increasing rural population of the region with the water it required.

As part of a massive land reclamation programme for developing the steppes and deserts into fertile fields, irrigated lands rose from 4.2 million ha in 1950 to 7.4 million ha in 1989. Water consumption for agriculture increased accordingly and the flow of Amu Darya and Syr Darya into the Aral Sea decreased from an average of 56 km³ at the beginning of the 1960s to around 6 km³ in the 1980s.

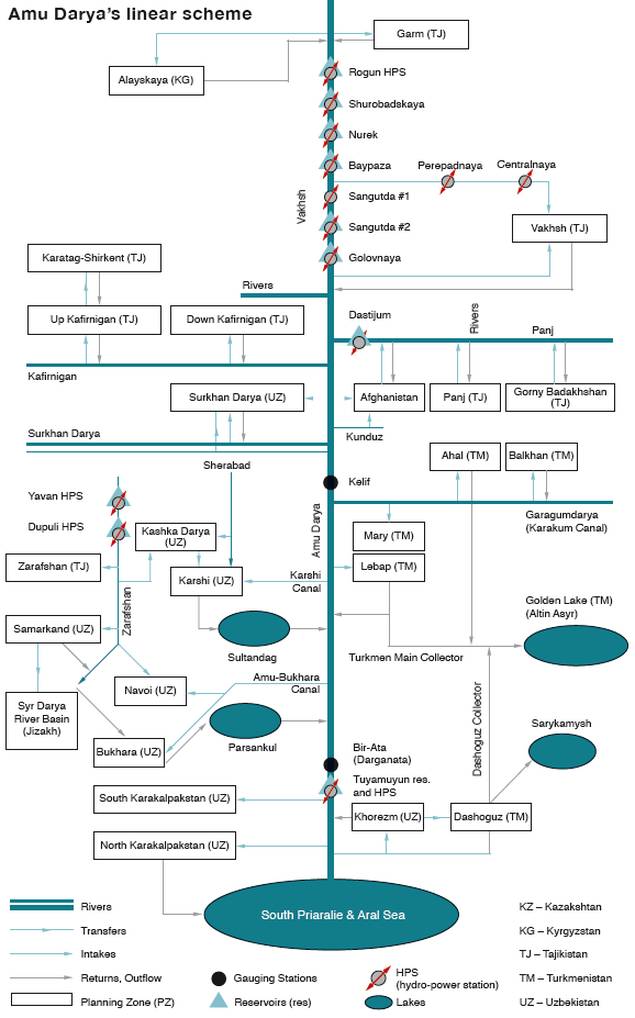

The reclamation of millions of hectares of additional agricultural and water-intensive cotton cultivation in the downstream republics was only possible with an extended water storage and distribution system. This required massive investments in canals, reservoirs and water pumping stations. In the lowlands, tens of thousands of kilometres of channels were built. Construction of the largest canal, the Karakum in Turkmenistan, started in 1954. It brings water from the Amu Darya at Kerki, Turkmenistan, westward to Mary, Ashgabat and ultimately to the regions close to the Caspian Sea. Other large irrigation structures include the Big Ferghana Canal (built in 1939), the Amu-Bukhara irrigation system, the Karshi Canal, bringing water from the Amu Darya to the Talimarjan reservoir, and water reservoirs like the Tuyamuyun in the Khorezm region, shared by Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. In some areas, reclamation of new irrigation land was possible only with the installation of pumps, especially in the Uzbek and Tajik SSRs, where they ensure at least part of the water supply to more than 60% of irrigated land.

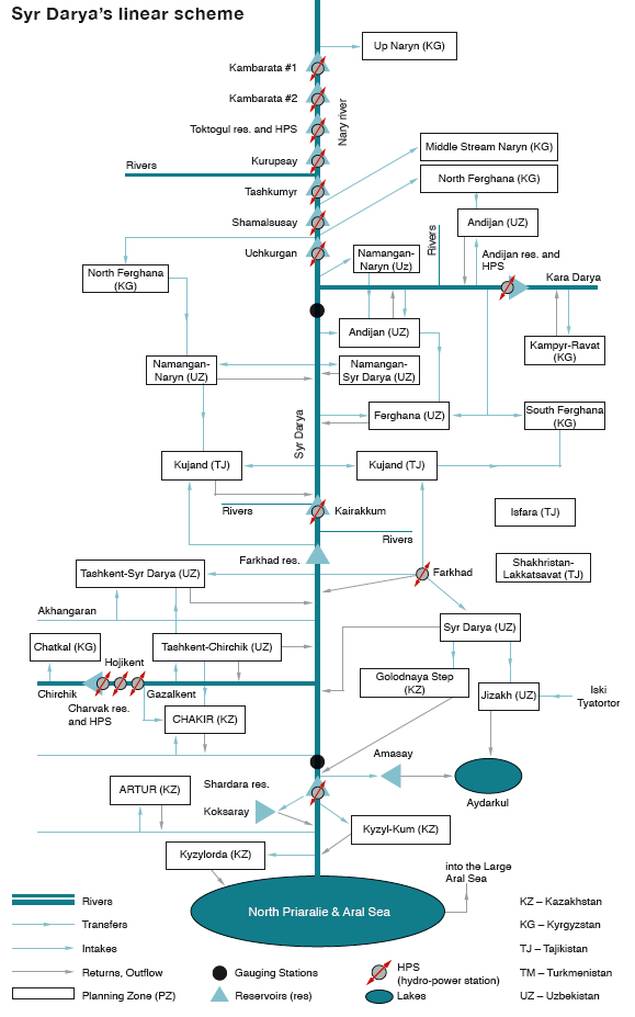

Also upstream, numerous reservoirs have been built in the mountainous regions to improve the regulation of the rivers for irrigation purposes. The biggest reservoir is the Toktogul reservoir with a storage capacity of 19.5 km³. It is part of Kyrgyzstan’s Naryn-Syr Darya cascade, a system of reservoirs and dams (Toktogul, Kurpsai, Tashkumyr, Shamaldysai, Uch-Kurgan) that regulates the flow of the Naryn River. In Tajikistan, nine operating reservoirs with a total storage capacity of 29 km³ were built. The two biggest ones are Nurek (10.5 km³) at the Vaksh River and Kairakum (4.16 km³) at the Syr Darya. The Nurek dam is the highest dam in the world (300 m).

In order to compensate the two Soviet republics for their losses in arable land and the costs of operation and maintenance of the facilities, a unified water-energy system was established. The reservoirs were constructed and operated primarily for downstream irrigation supply. Only at peak times was water released to produce electricity. In exchange for water withdrawal in the growing period in spring and summer, the downstream states delivered energy in the form of coal and gas in winter. This worked well, as both water and energy were centrally allocated by the government in Moscow.

In the official water governance structure of the Soviet Union, all water resources were controlled by the Union-wide Ministry of Melioration and Water Management (MinVodKhoz). In Central Asia, initially a regional agency (SredAzVodKhoz) was responsible for the whole Aral Sea Basin and also received orders from Moscow. Later, corresponding ministries in the Soviet republics were established, but their responsibilities were mainly restricted to the implementation of the decisions of the central MinVodKhoz in Moscow. The agency pursued an integrated basin-wide water and energy management approach in which each republic fulfilled a particular function. Water allocation was standardized with fixed schedules for republics, provinces and districts. Basin management administrations existed for some small rivers in Central Asia. However, they had a hard time competing with the province administrations, securing water foremost for the fulfilment of their own plans. The central MinVodKhoz itself had many subordinated agencies with overlapping functions and competencies, resulting in inconsistencies and ineffective implementation. It was responsible for planning, supplying, receiving, and controlling, so that all of the relevant water management functions were combined in one agency with minimal external oversight and control. The local water management authorities were also restructured under Soviet rule. During collectivization, all of the small land plots were combined into huge collective and state farms (kolkhoz and sovkhoz), which were in charge of the on-farm irrigation systems.[Bucknall et al. 2003, ISRI, Socinformburo, FES 2004, Obertreis 2011, Sehring 2002, Thurman 2002.]

The Soviet ideology of total human command over nature led to a belief in the ability to exploit natural resources, including water resources, indefinitely. Apart from a relatively low usage fee, water use was not paid for on a quantitative basis. This approach, along with the unclear and competing distribution of competencies among different state agencies, led to an erosion of the local sense of responsibility and a pattern of usage that disregarded the interests of others. The old norms and rules that ensured a relatively high yield with low water consumption eroded and water waste increased drastically.

In the 1970s, the ecological consequences of the massive agricultural expansion began to emerge: the shrinking of the Aral Sea, attendant desertification, the salinization of growing fields, water pollution by fertilizers and pesticides and water shortages in downstream areas. Some scholars in the Central Asian Soviet Republics started to carefully criticize wasteful water usage. The initial response was a perfect example of the Soviet belief in the supremacy of technology over nature. Instead of trying to increase the system’s efficiency, Soviet officials drafted plans to divert water from the north-flowing Siberian rivers Ob and Irtysh southward to Central Asia, where it would be used for irrigation and to refill the Aral Sea. The project enjoyed wide support among Central Asian water officials, but it also faced opposition. The plans were shelved in 1986, not because of the emerging environmental criticism, but because of the high costs. A few years later, after the famous «Aral-88» field mission in 1988[This expedition was organized by two journals and headed by the journalist Grigor I. Reznichenko. Almost 30 journalists, writers and scholars from Moscow and Central Asia, plus a representative of the prosecution and one of the Union-MinVodKhoz travelled through the whole basin for two months. The expedition helped to raise union-wide awareness of the Aral Sea crisis. See Obertreis 2011.], the Soviet government changed its approach and issued a decree on the improvement of the ecological situation in the Aral Sea Basin. It foresaw a reduction of new land reclamation and a reduction of water supply for irrigation areas by 30%. It was met by fierce resistance locally. Finally, the decree ordered only the reduction of water usage per hectare in the Aral Sea Basin by at least 15% by 1990 and by 25% by 2000. However, with the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the decree became obsolete, though the idea of diverting rivers from Siberia continues to be revived from time to time.[Obertreis 2011, Sehring 2002.]

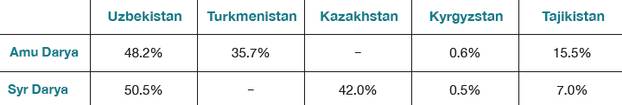

With the growing attention paid to the Aral Sea disaster, increased environmental awareness and glasnost, some institutional changes in water management were introduced in the 1980s. In order to better regulate the water distribution among the Central Asian Republics, a system of water quotas for the two great rivers was established (see table). These limited the amount of water each republic was allowed to use.

Water quotas in the Aral Sea Basin. Note: Afghanistan was not included in the arrangement

In addition, two river basin agencies (BVOs, basseynovaya vodnkhozyaystvennaya organisatsiya) for the Amu Darya and Syr Darya under the central MinVodKhoz were established and started working in 1988. They were put in charge of the entire rivers, regardless of administrative boundaries among republics or provinces. However, Turkmenistan refused to hand over its water intake point of the Karakum Canal at the Amu Darya. In 1990, Moscow’s MinVodKhoz was closed down and replaced by a «State Trust of Water Works Construction» (VodStroi), but the Central Asian Republics’ MinVodKhozes continued to exist.

Thus, water governance prior to independence was hierarchically and centrally organized and based on a Soviet Union-wide approach. It was a purely state-managed system without any economic mechanisms or stakeholder participation. It proved to be inefficient and was marked by wasteful usage patterns. The overuse of water led to a de facto scarcity of water in some regions, especially in the lower reaches of the rivers.[O’Hara 2000, Sehring 2002.]

Ecological legacies: environmental impacts of unsustainable water management

The overuse of water with ignorance of ecological limits and poor management during the Soviet period have since led to severe ecological consequences that the independent states have to face, the gravest being that 80% of the Aral Sea has turned into a desert. In addition, most of the irrigated land is plagued by salinization, waterlogging and water erosion. In the regions close to the Aral Sea, about 90% of the land is affected by salinization. The decay of soil quality requires additional large volumes of water to rinse away the salt and still reduces fertility. The regions at the middle and lower reaches of the big rivers suffer from water scarcity. The inflow of drainage water heavily contaminated with nitrates, organic fertilizers, and phenol has polluted the ground water. In the downstream regions of the Syr and Amu Darya, the provinces of Kyzylorda in Kazakhstan, Dashhoguz in Turkmenistan as well as Khorezm and Karakalpakstan in Uzbekistan, water is so polluted that it is unsuitable for either drinking or irrigation. At the Syr Darya, another potential health threat is radioactive pollution. Several uranium dumping sites are located close to the tributaries and are subjected to landslides.[MKUR 2006, Bucknall et al. 2003.]

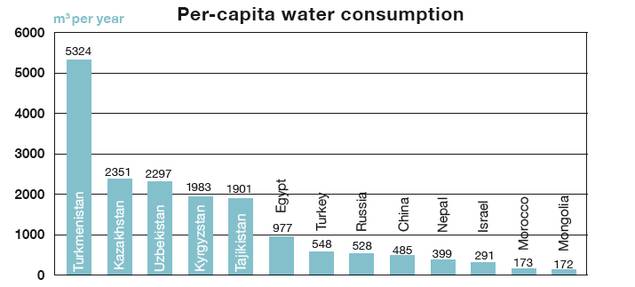

Decades of overuse of water in agriculture have shaped infrastructure, economic dependencies, social structures, usage patterns and traditions that are not easy to change. Therefore, these usage patterns continue to exist and have an impact even today. As described, during Soviet times water consumption did not have to be paid on a quantitative basis. Thus there were no economic incentives to limit consumption. This behaviour was aggravated by the Soviet ideology of human control over nature, which posits that nature is a mere means for human development and may thus be fully exploited. In addition, deteriorated infrastructure and inefficient irrigation techniques led to high water consumption. Instead of directing the water through closed pipes, water evaporates in open channels or trickles into earthen channels that are not lined. Outdated irrigation techniques with high water consumption and a high evaporation rate on the fields are still applied. The water loss from the huge Karakum Canal, with its unprotected banks, is estimated at one to two-thirds of the total flow.[Giese et al. 2004.] As a consequence, Central Asia has the lowest water use efficiency worldwide.[UNDP 2006.] Experts estimate that 50% to 80% of irrigation water is lost before reaching the fields.[EuropeAid 2010, World Bank 2004.] This leads to water use as high as 12 200 cubic metres per hectare-UNECE assesses water use in cotton irrigation even with up to 14 400–16 600 m3/ha. The following table shows that even compared with countries like Egypt or Turkey (themselves not the most efficient water users), per capita water use in Central Asia is considerably higher.[Bucknall et al. 2004, EuropeAid 2010, UNDP 2006, UNECE 2004.]

The main reasons for water scarcity in Central Asia are hence anthropogenic and rooted in wasteful overconsumption. This can actually be viewed as an opportunity. If water scarcity is a result of human activities, then we can improve the situation if we change our behaviour to more sustainable water usage and management.

Political legacies: conflicting usage interests of irrigation and energy production

In the Soviet Union, water and energy resources were managed in an integrated and top-down approach. Water resources were used for the best Union-wide benefit, to which each republic contributed. For Central Asia, the priority was cotton production, and therefore the whole Central Asian water management system was oriented toward this goal. In this respect, two important inter-republican governance mechanisms were established. One is the water-energy exchange system among the republics and the other are the water withdrawal quotas for each republic. Both have had a tremendous impact on today’s water usage patterns and policy strategies.

The quota system (see table on page 23) favours the irrigation needs of downstream countries. Compared to the data on water formation, the quotas show that those republics where most water resources originate-the Kyrgyz and Tajik SSRs-have the right to use only a small amount. The downstream SSRs of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan were entitled to use most of the water resources as most of the population of central Asia lived here and most of the cotton production of the Soviet Union took place in those republics. These quotas reflected historical and geographical conditions and actual needs. However, after independence, this arrangement did not reflect the needs and interests of the upstream countries, which now had to make best use of their resources to achieve national development. Nevertheless, the water quotas established even regarding smaller rivers are still in place. It is a highly political issue to assess and potentially re-negotiate them, as this exercise may ultimately affect the end the socioeconomic stability of each state.

The second important inter-republican governance mechanism was the establishment of the water-energy exchange system among the republics. As explained above, in the two upstream Kyrgyz and Tajik SSRs, huge reservoirs were constructed in order to store the water until it was needed in the downstream countries for irrigation. The original aim of the attached hydropower plants was only to provide energy in peak times, while the regular needs were covered by the unified energy system. Since independence, this has changed. The unified energy system broke down, and downstream states demanded market prices for their energy fossils. As a consequence, the upstream states have increasingly been using the dams for hydropower generation in order to cover their domestic energy needs.

Hydropower production is a non-consumptive water usage; the regulation in this case does not have to address the general amount of water withdrawal (like the quota system), but instead has to determine the time and seasonal amount of water release from the dams. This is a contested task, as there is a trade-off between water needs for irrigation and for hydropower production. Water is needed for irrigation purposes during the growing period in spring and summer, while energy needs are highest in winter. Thus, while the downstream states of Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan especially need water for irrigated agriculture, the upstream states of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan need the energy produced by water discharge in winter. Due to a lack of working management mechanisms, these rival usage interests have caused irrigation water shortages downstream as well as energy shortages upstream in recent years.

The Soviet legacy thus brought up two questions that had to be addressed by the new states: How to share water concerning the quantity of water withdrawals, and how to share water concerning the timing of water releases.

Transboundary waters in the six

states of the Aral Sea basin

While the region of Central Asia as a whole is affected by water overconsumption and pollution, consequences are specific for each country. The individual states are differently endowed with water and with other resources, so that the specific role water plays is different-depending on their upstream or downstream location, major water use interests and pollution problems. The specific country characteristics and interests have to be taken into account when approaching regional water problems in Central Asia. After the end of the Soviet Union, water usage became subordinate to a new regional situation with new national interests. These national interests will be described in the next chapter.

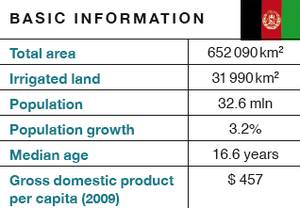

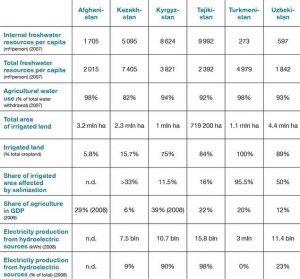

Afghanistan

Five river basins stretch over the territory of Afghanistan. Three of them cover the northern part of the country and are considered part of the Amu Darya Basin: The Panj-Amu Basin in the very northeastern area, the Haridud-Murghab Basin with the Murghab and Tejen rivers flowing into Turkmenistan, and the so-called Northern Basin, though its rivers still silt up on Afghan territory. Together, they cover about 37% of Afghanistan’s territory and account for almost 50% of the total surface water availability in the country. The Panj, the Amu Darya’s major tributary, forms the border of Afghanistan with Tajikistan. It is formed by the confluence of the Vakhan and Pamir Rivers. From the source of the Pamir, the Panj has a length of 1137 km. Important tributaries in Afghanistan are the Kunduz, the Koksha, and the rivers of Badakhshan.

There is limited data on how much water exactly is formed and used in the Afghan part of the basin, since the monitoring system broke down in the late 1970s due to the civil war. Based on previous data and recent studies, experts estimate that between 14 and 27% of the Amu Darya’s flow is formed in Afghanistan and that it currently uses about 2 km³ (3%) of the average annual river discharge. Due to topography and climate, arable land is scarce and 94% of agriculture depends on irrigation. Consequently, agriculture is the main water user at 95%. The irrigated area in the Amu Darya Basin encompasses around 1.16 million ha (about 42% of the total irrigated area in the country), mainly subsistence agriculture, which most of the rural population of Northern Afghanistan relies on. Apart from that, there is a growing cultivation of poppy.

The agricultural sector’s contribution to Afghanistan’s GDP amounts to 33% (2008), but it absorbs about 60% of the labour force (2008). Therefore, the agricultural sector is considered important for the reconstruction and development of Afghanistan by the Afghan National Development Strategy and international donor agencies. Efforts toward reconstruction, poverty reduction and rural development include the rehabilitation of irrigation systems, re-cultivation of former irrigation land, and construction of small HPPs. All these efforts will increase water usage in Afghanistan, though not dramatically. In a study for the World Bank, Ahmad and Wasiq estimate that the technically feasible expansion and reconstruction of irrigation schemes would increase water use by 0.8 to 1 km³ per annum. A short-term increase beyond the levels of the 1980s seems unlikely. But under conditions of increasing water shortage in downstream areas, even a slight increase raises concerns.

Despite being an integral part of the basin, Afghanistan is not included in any regional agreements. Agreements between Russia and later the Soviet Union and Afghanistan on border rivers did not include provisions on water distribution. When the Soviet Union established the water limits for Syr Darya and Amu Darya, it did not consider Afghanistan, but only assumed that Afghanistan used 2.1 km³ of water annually. In addition, Afghanistan has not been involved in any regional institutions on water management since the Central Asian Republics gained their independence.[Ahmand and Wasiq 2004, CPHD 2011, FAO 2010, King and Sturtewagen 2010, AQUASTAT, WDI.]

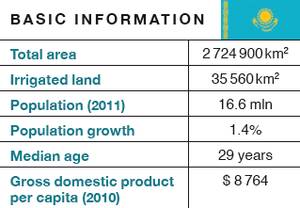

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan is the largest of the Central Asian countries. More than two-thirds are covered by deserts and semi-deserts; the rest is mainly steppes and low hills, with some high mountain ranges at the eastern and southeastern borders.

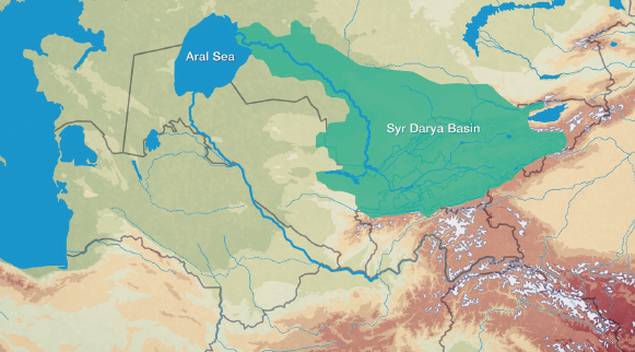

Kazakhstan has 48 800 lakes and reservoirs. The largest inland body of water is Lake Balkhash (18 810 km²), which consists of a western part with fresh water and an eastern part with salt water. The average depth of the lake is only six meters. The country has eight river basins with over 7 700 rivers. The biggest ones are the Syr Darya, the Irtysh and the Ishim (flowing into Russia), the Ural (flowing from Russia), Chuo and Talas (flowing from Kyrgyzstan). Seven of the eight basins are transboundary. The main water inflow comes from Kyrgyzstan, China, Russia and Uzbekistan. Almost half of the surface water available in Kazakhstan (about 100.5 km³) originates in one or more of its neighbouring countries.

The Kazakh part of the Syr Darya Basin stretches along 1 127 km from the Shardara reservoir on the border to Uzbekistan, through the southeastern part of the country to the Aral Sea. Seventeen percent of the Kazakh population lives in this basin, most in rural areas. Thus, only a small part of the country belongs to the Aral Sea Basin (345 500 km² of 2 224 400 km²). Nevertheless, being a downstream country, Kazakhstan relies on timely water discharge from the upstream water reservoirs in Kyrgyzstan and the passage through Uzbekistan during the growing period. As these releases could not always be ensured, Kazakhstan built the Koksaray reservoir. With this additional reservoir just downstream from the Shardara reservoir, it is able to store water released in winter until spring and reduce harmful winter floods downstream, as well as dependence on upstream water releases. While these measures have eased the situation at the lower reaches of the Syr Darya in Kazakhstan, they present a risk for the Aydar-Arnasay lakes system in Uzbekistan. This is a wetland that has emerged from overflow of water in winter from the Shardara and drainage water and serves as an important habitat for water birds. In addition, a newly built reservoir allowed Uzbekistan to use the overflow water for irrigation. With the Koksaray reservoir, Kazakhstan can store the previously released water itself for later usage or flow into the Aral Sea, putting this newly created but ecologically important wetland at risk. Therefore, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have reached an agreement on an annual minimum flow. Kazakhstan has undertaken considerable efforts to revive the Northern Aral Sea (see p.20/21). For Kazakhstan, the situation in the Ili-Balkhash Basin is of much greater concern than that of the Syr Darya. This basin is shared with China, which is increasing its water usage, putting the fragile ecological balance of Lake Balkhash at risk.

Kazakhstan is endowed with abundant natural resources, including significant deposits of oil, natural gas, uranium, chromium, lead, zinc, manganese, and copper. Oil and gas production have increased rapidly over the last decade and, with minerals, provide most of the revenues. In contrast, agricultural production accounts for only 6% of GDP (2009) but for 15% of the workforce (2008). Arable land constitutes 8.4% of the land. It is important in the poor, rural south of the country, where cotton and rice production take place.[UNECE 2008, UNECE 2011, WDI, AQUASTAT.]

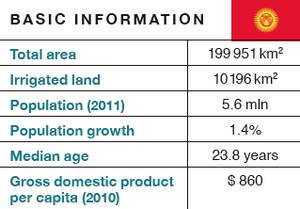

Kyrgyzstan

High mountains cover about 65% of Kyrgyzstan, which is located at the juncture of the Tian Shan and Pamir mountains. More than 3 500 rivers have their origin in its territory, which is divided into six river basins. The biggest part of the country belongs to the Syr Darya Basin. Its tributaries are the Naryn (807 km), the Kara Darya, and the Chatkal, which flow from Kyrgyzstan into Uzbekistan. Other transboundary rivers are the Chu and Talas, flowing into Kazakhstan, and the Aksu feeding the Tarim River in China.

There are 1 923 lakes in Kyrgyzstan, more than 80% of which are located above 3 000m. Lake Issyk-Kul-located at 1 608 m in the Tian Shan mountains-has a surface area of 6 249 km². It is the country’s largest lake and the second-largest alpine lake in the world. Glaciers occupy about 4% of the country. Seasonal snowmelt and runoff from melted glaciers account for up to 80% of the rivers’ total flow.

Due to the mountainous topography, only 7% of the total land area is used for crop cultivation, while 44% is used as pasture for livestock. Animal husbandry is a significant part of the agricultural economy. Most cultivated land is irrigated so the agricultural sector consumes more than 90% of the water. The main cropland areas are the Ferghana Valley and the Talas and Chu provinces. Main crops include fodder, wheat, corn, rice, tobacco, cotton, vegetables and fruits. The main agricultural export products are cotton and tobacco.

Though the share of agriculture in GDP decreased from 37% in 1991 to 29% in 2008, it remains important, especially for the two-thirds of the population living in rural areas. The agricultural sector employs 36% of the labour force.

Nevertheless, the priority water usage is the production of electricity. Although to date only a small portion of their potential is used, dams provide more than 90% of the country’s power. Kyrgyzstan has also been exporting 2–2.5 billion kWh/year to China, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. Hydropower plants produce 10.7 billion kWh of electricity per year. The five biggest plants, which are all located on the Naryn, produce 97% of the country’s hydropower.

Thirteen artificial reservoirs with a storage capacity of more than 20 km³ have been created to regulate the water flow, mainly for the purpose of hydropower production, irrigation and flood protection. The biggest reservoir is the Toktogul (see page 18). Other dams and reservoirs are the Kirov on the Talas River and the Orto-Say on the Chu River. When constructed during the Soviet Union era, these reservoirs were designed not for the benefit of Kyrgyzstan, but for irrigation in the downstream republics. Indeed, Kyrgyzstan lost 21 100 ha of cultivated land when the dams were built. After independence, it could use and sell the electricity from the hydropower plants, but also had to bear the full cost of operating and maintaining the dams. For this reason, Kyrgyzstan has regularly requested fair cost-sharing mechanisms.

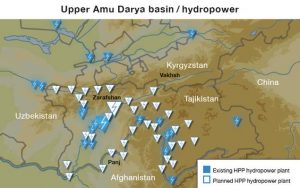

After the delivery of coal and gas from the downstream countries ceased in the 1990s, Kyrgyzstan increased its water discharge in winter to replace them. In addition to the existing power plants built in the Soviet period, several new ones have been constructed and more are planned. The biggest ones are Kambarata-1 and Kambarata-2 on the Naryn River. The 360 MW Kambarata-2 project started in 1986. After independence, construction slowed as financing dried up. But thanks to a Russian loan, the first unit began operating in November 2010. The construction of Kambarata-1 is underway in cooperation with the Russian energy company INTER RAO UES. Its capacity is expected to reach 1900 MW and it will cost about $2 billion. In addition, there are more than 200 small hydropower plants. Many of them were built in Soviet times, and some were added after independence with the support of international assistance in order to ensure energy supply for small and remote villages.[Antipova et al. 2002, Giese et al. 2004, Sehring 2009, UNECE 2008, WDI.]

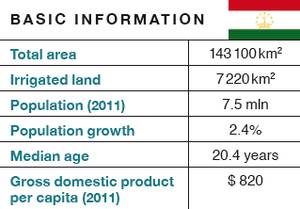

Tajikistan

Tajikistan is a mountainous country; the Tian Shan, Gissar-Alay and Pamir mountain systems cover about 93% of the country with half of it lying above 3 000 m. Lowland areas are confined to river valleys in the southwest and to the Ferghana Valley in the north.

Tajikistan is rich in water resources. It has about 1 300 lakes, most of which are located above 3 000 m in the eastern Pamir region. The largest one is the saltwater Lake Karakul (380 km²), at an elevation of 3 914 m. The deepest freshwater lake is the 490m-deep Lake Sarez (3 239 m above sea level, 86.5 km²), which was formed after an earthquake in 1911 triggered a landslide that formed a natural dam blocking the Murghab River.[This river called Murghab is not to be confused with another river named Murghab that is shared between Afghanistan and Turkmenistan in the Harirud/Murghab Basin.] Experts fear that the natural dam might breach or that landslides could cause a tidal wave over the dam in case of an earthquake, which could result in a catastrophic flooding along the Panj and Amu Darya. Glaciers cover 6% to 8% of the state, and 90% of them lie in the Amu Darya Basin.

More than 25 000 rivers flow in the country. Tajikistan forms part of both the Syr Darya and the Amu Darya Basins, which cover practically the entire country. The rivers Vakhsh, Kafirnigan and the Panj, the border river with Afghanistan, are the main tributaries to the Amu Darya, fed by glacier and snowmelt from the high ranges of the Pamir mountains and draining more than 75% of the country. In the northern Ferghana Valley, the Syr Darya crosses 195 km through Tajikistan. Another important transboundary river is the Zarafshan, which runs through central Tajikistan into Uzbekistan.Tajikistan has nine operating reservoirs, most of them along the Vakhsh River, which feeds the Amu Darya.

Even though only 5% of Tajikistan’s land area is arable, irrigation agriculture plays an important economic role and produces 90% of the agricultural output. More than 60% of the land depends at least partly on pumped irrigation, which makes it more expensive than in other Central Asian countries. Cotton constitutes 43% of all planted crops. Though the share of agriculture in GDP declined from 37% in 1991 to 22% in 2009, cotton still yields 11% of all exports, which makes it the most important export after aluminium and electricity. As for the workforce, about 31% (2004) is officially engaged in agriculture.

Tajikistan’s main water usage is hydropower production. After Russia, Tajikistan is the second largest producer of hydropower in the CIS; on a per capita basis it is the biggest worldwide, despite the fact that at present only about 5% of the hydropower potential is exploited. The biggest hydropower plants are: Nurek (3 000 MW), Sangtuda 1 (670 MW), Sangtuda 2 (220 MW), Baipazan (600 MW), Golovnaya (240 MW) and Kairakum (126 MW).

But this production is not enough to meet the energy demands of the country. Like Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan used to receive coal and gas in the Soviet unified system and faces a severe energy crisis today. In winter, rural areas usually have power for only a few hours a day. In the winter 2010/11, even in the capital the electricity supply was restricted. The problem is aggravated by the fact that much of the energy that is produced is consumed by the big aluminium plant TALCO or gets lost in inefficient transmission systems. In this respect, the government strives to make more use of its rich hydropower potential. In addition to about 250 small hydropower plants, several new large one have been constructed since independence, such as the Sangtuda 1 and 2 on the Vakhsh River, supported by Russian and Iranian investments.

The Tajik government has also revived old plans to build the highest dam in the world at Roghun, with a planned height of 335 m and a power plant designed to produce 3 600 MW of electricity. The construction of this dam was started in the 1980s, but construction stopped and it was damaged by a flood in the early 1990s. In October 2004, the Tajik government entered into an agreement with the Russian company RusAl to construct the first stage of Roghun, but due to disagreements about the height of the dam, it was cancelled by Tajikistan in August 2007. In 2009, Tajikistan decided to finance the dam itself. In January 2010, it introduced shares of Roghun with a massive campaign urging the population to buy them. In the following months, shares worth $ 185 million were sold. After concerns were raised by downstream countries, Tajikistan agreed to carry out an independent assessment of the technical feasibility and the social and environmental impacts of the project by international experts financed by the World Bank. Until the results are released in mid-2012 at the earliest, Tajikistan is committed not to resume construction.[AsiaPlus 2011, BIC 2011, Sehring 2009, UNDP 2003, UNECE 2004, WDI, WRI.]

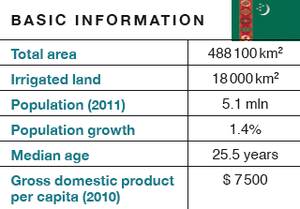

Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan’s territory is covered for 80% by the vast Karakum Desert. In the southwest, along the border with Iran, and in the east, along the border with Uzbekistan, lie some mountain ranges. The cultivable area constitutes between 4% and 14 % of the country.

Internal river runoff originating in the country is negligible, with an estimated 1 km³ per year. There are only some small, internal rivers in the Kopetdag mountains at the country’s southern border. Small transboundary rivers are the Atrek flowing from Iran, the Murghab from Afghanistan and the Tedzhen (flowing from Afghanistan through Iran into Turkmenistan). The Amu Darya provides almost 90% of the country’s water via the Karakum Canal, which is the largest and most important water infrastructure in Turkmenistan. It runs from the border with Uzbekistan across the country to the western regions near the Caspian Sea. With a length of more than 1 300 km, it is the longest canal in the world. Further downstream in the north of the country, the oasis region of Dashoguz is fed by the Tuyamuyun reservoir located at the border of Uzbek territory. Furthermore, 18 smaller reservoirs were constructed mainly for irrigation purposes, with a total capacity of 2.89 km³. The largest reservoir is the Hauz-Khan reservoir on the Karakum Canal, with a capacity of 0.875 km³.

About 80 artificial drainage lakes were created by the outflow of salty drainage waters from irrigated fields. The largest one is the Saragamysh Lake (8 km³), located about 200 km southwest from the Aral Sea. It was formed in 1971 as a result of the flooding of several small lakes in the Sarykamysh depression, which were periodically filled by Amu Darya waters, and since then has become a large drainage water body, used as a discharge collector of salty irrigation water. In 2009, the Turkmen government started the construction of the Altyn Asyr Lake (Golden Age Lake), later renamed Grand Turkmen Lake, in the Karashor salt depression in the northern part of the country (about 350 km north of the capital Ashgabat). Old riverbeds and new canals with a total length of more than 1 000 km are expected to carry drainage water from different parts of the country that currently is discharged either back into the Amu Darya or into the Sarygamysh Lake. Once filled, the Grand Turkmen Lake is expected to be 103 km long and 18.6 km wide, with a capacity of 132 km³ and a surface of about 1 916 km². The government plans to develop it into a recreational zone, with some of its waters used to irrigate new pastures and orchards. However, experts have predicted the lake would have negative environmental effects and would reduce return water flows into the Amu Darya.

Turkmenistan possesses the world’s fourth-largest reserves of natural gas and hardly any arable land. Consequently, the economic significance of agriculture is limited to 12% of the GDP (2009). However, more than half of the population lives in rural areas, and 32% (2004) are employed in agriculture. As in the other Central Asian states, irrigation is the main water consuming sector, with about 92%. Virtually the entire cultivated area is irrigated. An extensive network of canals with a total length of about 39 000 km have been been built, most of which are unlined, inefficient earthen canals. During Soviet times, the emphasis was on cotton cultivation. After independence, irrigation areas were expanded in order to grow more food crops and increase self-sufficiency.

There is a little hydropower potential in the country (estimated at 5.8 GWh), but only about 0.7 GWh (1993) is produced. Given the rich hydrocarbon resources, there is no interest in its exploration.

Due to its extremely arid climate, water is a critical resource for the country. This was already acknowledged in an old Turkmen proverb saying: «A drop of water is a grain of gold», which is also the motto of a national holiday celebrated annually on the first Sunday in April.[Kostianoy et al. 2011, Sehring 2002, UNDP 2010, WDI, AQUASTAT.]

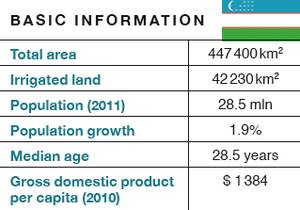

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan is one of the world’s few double-landlocked countries. To reach the nearest sea from there requires crossing Turkmenistan and Iran. Almost 80% of it is covered by desert. Mountains in the eastern regions reach an altitude of more than 4 000 m. The Ferghana Valley in the east and the Khorezm region in the north-west are the main areas of irrigated agriculture.

Like Tajikistan, Uzbekistan is bisected by both the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya. The Syr Darya crosses Uzbekistan in the east, feeding the fertile Ferghana Valley. The Amu Darya River Basin covers most of the country and includes the Surkha Darya, Sherabad, Kashka Darya and Zarafshan rivers. In addition, there are more than 17 000 small rivers and approximately 500 lakes in Uzbekistan, most smaller than one square kilometre. Only about 10% of its water is generated within the country, so Uzbekistan is highly dependent on inflows from Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Afghanistan.

In addition to the natural water bodies, 51 operating reservoirs are used for irrigation purposes, though some of the larger ones are also used for power generation. About 28 000 km of channels serve the irrigation system.

Though the country has rich gas deposits and only 10% of its land is arable, agriculture is an important economic sector, and irrigation consumes about 90% of total water usage. Cotton is the most important cash crop. In 1980, about 2 million tons of cotton were produced in Uzbekistan. After independence, the government made efforts to restructure the agricultural sector to grow food crops and reduce water consumption, which led to a decline in cotton production by about one-third. It has reduced the area of cotton production from 50% of the total irrigated area in the early 1990s to 30% today, substituting it with food crops like cereals and vegetables and forage. In 2010, cereal production in Uzbekistan reached 7 million tons compared to 1 million tons in 1991. Uzbekistan has also invested in new technologies that reduce water usage and international donors have supported this with about $1 billion over the last 10 years. Through these measures, the country was able to reduce water consumption and achieve food self-sufficiency. Uzbekistan is still among the six main cotton producing countries and the second-largest exporter of cotton in the world.

The share of agriculture in the GDP decreased from 37% in 1991 to 20% in 2009. But agricultural production still constitutes about 8% of the country’s total export income. Almost two-thirds of Uzbekistan’s population live in rural areas and are directly dependent on water for their livelihood. About 25% of the labour force works in the agricultural sector (2004).

Uzbekistan has voiced concern over the construction of new dams and hydropower plants on the upstream tributaries of the Syr Darya and Amu Darya. It has expressed fears that the filling of the reservoirs and then the operation of the dams in energy mode (water discharge in winter) would drastically reduce the amount of water it receives for irrigation during spring and summer. Uzbekistan is also vulnerable to natural disasters and worries that an earthquake could destroy a dam.

Meanwhile, Uzbekistan also uses water for hydropower production on a small scale. Twenty-eight small and medium-sized hydropower stations produce 12.5% of its electricity. The Uzbek government plans to build more.[WDI, WRI, UNCTAD, UNECE 2010.]

IFAS: a history of post-Soviet cooperation

Over the last 20 years, the Central Asian states have signed numerous agreements and documents on transboundary water management. They established an organizational structure for regional water governance and to address the Aral Sea disaster. The core platform of regional water cooperation is IFAS-the International Fund for Saving the Aral Sea, of which all five former Soviet republics are members.[The following chapter is based on ec-ifas.org, icwc-aral.uz, Dukhovny and Sokolov 2003, IFAS 2003, Le Moigne 2003, Libert et al. 2008, Sehring 2002, Sehring 2007, Shalpykova 2002, Weinthal 2001.]

IFAS: organizational structure

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the five newly independent Central Asian states saw the need to cooperate on their shared water resources. In September 1991, their ministers of water resources issued a statement in which they declared that joint management of water was necessary to solve the region’s water problems and should be carried out based on the principles of equality and mutual benefit.

On 18 February 1992, the five ministers signed the «Agreement on cooperation in joint management, use and protection of interstate sources of water resources». It declared that the quota system established by the Soviet Union (see page 22) should remain in place until a new strategy was developed, and it founded a joint body, the Interstate Commission for Water Coordination (ICWC). This agreement was followed by numerous other ones, such as the 1993 presidential «Agreement on joint actions on resolving the problems related to the Aral Sea and its coastal zone on environmental sanitation and socioeconomic development in the Aral Sea region», the Nukus Declaration of 1995, the 1999 agreement «On the status of IFAS and its organizations», and others.

The ICWC (Interstate Commission for Water Coordination) was the first regional institution set up after independence. Its main tasks are to control the regulation, efficient use and protection of the waters, to develop a regional common water management policy and to determine annual limits of water use for each state. Its members are the heads of the respective national water ministries or departments, who meet every quarter to determine the exact water distribution-i.e. the translation of the general quotas into exact amounts based on water flow measurements and weather forecasts. Meetings of the ICWC are chaired by the member countries on a rotational basis. All decisions are made unanimously. Operative bodies of the ICWC are the secretariat in Kujand (Tajikistan), a scientific information centre in Tashkent (SIC ICWC) with branches in all member countries and the two river basin organizations (BVOs), which had already been established by the Soviet government. The headquarters of the BVO Syr Darya is in Tashkent (Uzbekistan); the one of the BVO Amu Darya is in Urgench (Uzbekistan).

In 1993, ICAS (Interstate Council for the Aral Sea Basin) was founded with the EC (Executive Committee) as its executive agency. It consisted of five members per republic who met every half year and decided about the plans developed by the EC, which formulated principles, projects and measures. The ICWC was integrated into ICAS. Also in 1993, the International Fund for Saving the Aral Sea (IFAS) was set up in Almaty. All member states were expected to pay 1% of their state expenses to this fund per year. Its Executive Committee (EC IFAS) consists of two representatives for each of the five states. Initially, the role of IFAS was primarily to generate funds from member state fees and donor assistance, while EC ICAS was in charge of the Aral Sea Basin Program (ASBP, see below).

In 1994, a new ecological commission was affiliated, the ICSDSTEC (Interstate Commission for Socioeconomic Development and Scientific and Ecological Cooperation), later renamed the Interstate Commission on Sustainable Development (ICSD). Its main objective is the coordination and supervision of cooperation in the field of environmental protection and sustainable development in Central Asia. The ICSD meets twice a year with the chair rotating among its member states. A Scientific Information Centre (SIC ICSD) is based in Ashgabat.

In 1997, the regional institutions were restructured following an evaluation of the first phase of the ASBP that advised a strengthening of the regional institutions. Because of overlapping responsibilities, ICAS and IFAS were combined under the name IFAS. The chairmanship of IFAS has since then rotated among the presidents of the five member states. The EC IFAS is accordingly located in the respective country. Thus, the Executive Committee has been located in Almaty (1993–1997), Tashkent (1997–1999), Ashgabat (1999–2002), and Dushanbe (2003–2009; the planned move to Bishkek did not take place due to political turmoil in 2005). Since 2009, it has been based in Almaty. Another decision concerned the fees of the member states. As it became obvious that none of the states had fulfilled its financial commitments, contributions were lowered to 0.3% of the state expenses for the rich countries downstream and to 0.1% of state expenses for the poor countries upstream.

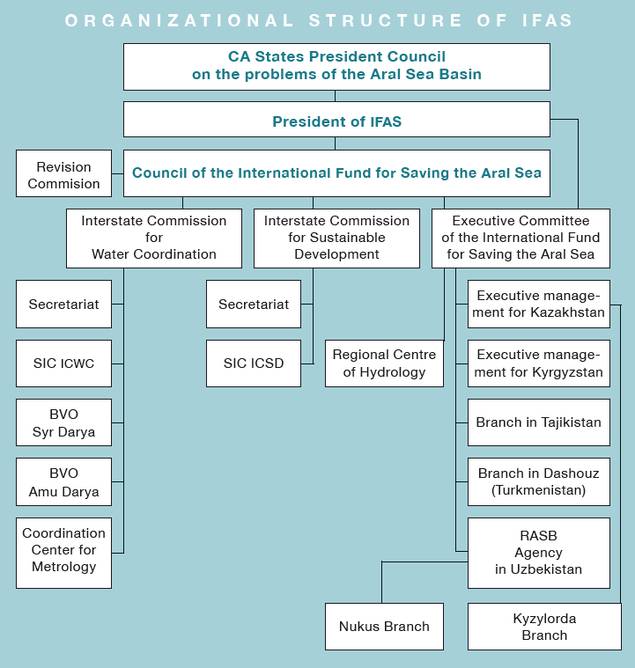

In 2002, the IFAS Board decided to establish a Regional Centre of Hydrology (RCH) and attach it to EC IFAS. Its main purpose is to improve the system of hydro-meteorological forecasting, environmental monitoring and data exchange among the national hydro-meteorological agencies in the region. RCH is currently located in Almaty, Kazakhstan. Since then, the structure of the IFAS has read as follows:

The Aral Sea Basin Program (ASBP)

One of the main activities of IFAS is the Aral Sea Basin Program (ASBP). This is the main long-term action program in the region in the field of sustainable development, in particular for the sustainable management of water resources and related aspects. The program includes national and regional projects. It has its roots in the first UNEP-Soviet diagnostic study of the Aral Sea that was conducted in 1988-1991 in collaboration with the Soviet government. In 1992, the preparation of the ASBP began, and after ICAS and IFAS were founded in 1993, the program was officially launched as a joint effort of the World Bank, UNDP and UNEP. Its main goals were:

- Stabilizing the environment in the Aral Sea Basin;

- Restoring the disaster zone around the Sea;

- Improving management of transboundary waters in the basin;

- Developing the capacity of the regional organizations to plan and implement the program.

It developed into the most comprehensive international program addressing the Aral Sea crisis and enjoyed the active support and involvement of numerous multilateral and bilateral donors. These included the Asian Development Bank, UNESCO, the European Union and the governments of the USA, Canada, the Netherlands, Switzerland and others. In the first project phase, $280 million in credits and $48 million in grants were allocated.

In 2002, a second phase called ASBP-2 was developed after the five heads of state met in Dushanbe on 6 October 2002. IFAS planned to tackle a wide range of environmental, socioeconomic, water management and institutional problems for the period 2003-2010. According to EC IFAS, the contribution from the IFAS member states to the implementation of activities was over $1 billion, with additional financial support from donors, including UNDP, the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, USAID, as well as the governments of Switzerland, Japan, Finland, Norway and others.

The challenges of effective regional water cooperation

IFAS is the only regional organization in which all five Central Asian states are members. It is proof that shared water resources can foster cooperation. In contrast to many other regional Central Asian organizations, IFAS and its subordinated bodies have functioned for 20 years. It is well understood in the region that programs and agreements did not always meet the expectations of the member countries and the donor community. This is not surprising giving the conditions under which the regional water cooperation had to evolve in Central Asia. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Central Asian countries had to develop new structures, institutions and policies to govern the formerly Moscow-managed natural resources in a situation of economic and political collapse and without the necessary technical, financial, administrative and political capacities at their disposal. These conditions led to weaknesses in the regional structure like the lack of a coherent legal foundation and an effective organizational structure, weak coordination and inefficient implementation of decisions. And it must not be forgotten that there are always risks and benefits involved when it comes to long-term commitments on all sides. However, the fact that IFAS has been instrumental in guaranteeing peaceful and prosperous development should not be underestimated.

When trying to assess the performance of IFAS until today, it is useful to look at the Declaration of the Heads of States of all Central Asian countries, which was issued in Almaty in 2009 (see p. 53–55). They express very clearly that IFAS has more potential and subsequently they tasked the EC IFAS with working out proposals for an administrative reform of the institutions in order to improve their performance. The heads of states also believe in international cooperation and invited the international donor community to become more active in working out joint programs and solutions for the water issues in Central Asia. Better regional cooperation and the creation of trust in the field of transboundary water management is a long-term process. Experience in other river basins shows that it often took decades to develop the necessary trust and adequate working mechanisms for effective joint cooperation. In this respect, IFAS is still a young organisation in its institutional development.

Additional efforts for water cooperation

Apart from the agreements and regulations related to IFAS, the Central Asian states have made a number of additional multilateral and bilateral efforts to jointly regulate water use.

In 1996, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan signed a separate permanent agreement for an equal distribution of water resources. It states that 50% of the Amu Darya flow at the Kerki gauging station is allocated through the Karakum Canal to Turkmenistan, and the rest to Uzbekistan.

In 1998, the governments of Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic and Uzbekistan signed an «Agreement on the Use of Water and Energy Resources of the Syr Darya Basin». This agreement provided that Kyrgyzstan would discharge water from its reservoirs in summer for the downstream states of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, while these would deliver fuel to Kyrgyzstan in winter, so that it does not need to produce hydropower. In 1999, Tajikistan joined the agreement so that the working regime of the Karakum reservoir could be included. The agreement requires annual protocols to define exact discharge times and amounts, as well as the price of energy to be sold to the downstream countries during the summer period and on the transfer prices of coal, gas and electricity. The agreement worked well for some years, but in others the promised coal and gas were not delivered to Kyrgyzstan, which then released water in winter to make up for the energy shortfall. From 2003 on, the parties failed to agree on annual protocols. Instead, bilateral and ad-hoc regulations were followed. These are more opaque, do not provide for long-term planning and preclude any possibility of sanctions in case of non-compliance.

The consequences were painfully visible in the winter of 2003/04. Since the summer of 2003 witnessed extraordinary high precipitation downstream and less water for irrigation was required, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan ceased to deliver the agreed amounts of fossil fuels the following winter. In order to compensate for the loss, Kyrgyzstan produced more hydropower, releasing much more water than usual from the Toktogul reservoir that winter. The flow could not be absorbed by the frozen riverbed of the Syr Darya or the downstream reservoirs and it caused severe flooding in Kazakhstan and fears of dam failure at the Shardara reservoir, where 2 000 people were evacuated.

The failure of the agreement affects not only energy security of the upstream countries in winter and irrigation water security downstream in summer, but also the safety of the dams. During the last few years, the downstream states only minimally participated in the cost of maintenance and renovation works of the upstream reservoirs, the cost of which is covered by the relatively poorer Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. The Chu-Talas agreement, which includes cost-sharing mechanisms between Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, is an exception to this overall trend and shows that it can work. For the Syr Darya, it is astonishing that even an obvious win-win arrangement like the water-energy trade was not perceived as having mutual benefits, but rather viewed with mistrust and suspicion. This can be explained by the lack of previous positive examples of cooperation in other fields so far, which led to a preference for self-reliance.

In 2005, another effort was undertaken to tackle water-energy issues in a cooperative manner. With support from the World Bank, a draft framework agreement on a «Water-Energy Consortium» was prepared in the framework of the Central Asia Cooperation Organisation (CACO), a short-lived regional organization that later was integrated into EurAsEC.[The EurAsian Economic Community (EurAsEC) is an international economic organization aimed at economic coordination and creating a joint customs union among its members. The member states are: Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan (suspended).] However, due to different national interests and weak commitment on the part of the Central Asian countries involved (Turkmenistan was not a member of CACO), the process stalled and donors ended their support.

The 2009 summit and the reform process

2008 was an extremely water-stressed year, in particular for the Syr Darya Basin. A very cold winter in 2007/08 forced Kyrgyzstan to discharge more water than usual for energy production. It was followed by an unusually dry spring and summer, in which the downstream states could not receive sufficient water for irrigation due to the low water level in the Toktogul reservoir. It became obvious that the existing institutions and regulations were not able to prevent or even manage such a crisis. It was only thanks to an extraordinary meeting of the Central Asian presidents in October 2008 that a preliminary solution was found for the upcoming year, with deliveries of extra energy from downstream countries to upstream ones in winter in exchange for sufficient water releases in summer. In this situation, Kazakhstan took over the rotating presidency of IFAS and the EC IFAS moved from Dushanbe to Almaty.

On 29 April 2009, the Central Asian heads of states met for an IFAS summit in Almaty. In their joint statement, they emphasized the importance of IFAS, expressed their readiness to improve its organizational structure and tasked IFAS’ bodies to develop a third phase of the Aral Sea Basin Program.

In 2010, EC-IFAS started the elaboration of the third phase of the Aral Sea Basin Program (ASBP-3), covering the years 2011–2015. This time, the project preparation process involved extensive consultation with national and international experts. EC IFAS was in continual dialogue with the donor community (in particular with the World Bank, the European Union, USAID, GIZ, and SDC) in order to solicit their comments and ideas on program priorities and project proposals. Several coordination meetings with regional organizations and key donors were held. Additionally, the World Bank, GIZ and the European Union supported the preparation with consultants. The ultimate objective of ASBP-3 is to improve the socioeconomic and environmental situation by applying the principles of integrated water resources management, to develop a mutually acceptable mechanism for a multi-purpose use of water resources and to protect the environment in Central Asia while taking into account the interests of all the states in the region.

ASBP-3 works in four directions:

1. Integrated water resources management;

2. Environmental protection;

3. Socioeconomic development;

4. Improving institutional and legal instruments.

Based on these objectives, a list of criteria for project proposals to be included in the program was agreed upon during the consultation:

- National projects to be implemented within one state and primarily financed from the national budget;

- Regional projects to be implemented in the territory of two or more states;

- Meeting the ASBP goals and objectives;

- Meeting one of the directions of ASBP;

- Linking with the corresponding national and regional policy goals and programs.

EC IFAS received a total of 335 project proposals. In a consultative process with the donor community and all stakeholders, the proposed projects were put in clusters and were aggregated. As a result, 45 projects were identified and are now part of the ASBP-3. These projects are ready for financing and EC IFAS is looking to raise the required funds for them.

In December 2010, the draft ASBP-3 was presented to the donor community and the IFAS Board. Donors and implementing agencies have expressed their full support for ASBP-3 in a joint statement, which appreciates the close cooperation between IFAS and the donor community.

The Role of International Players

The previous chapter showed that international players have been involved in transboundary water cooperation since the Central Asian states became independent. It is impossible to describe all of their activities here. But this chapter will give some examples of key donors and their actions beyond their direct support to IFAS and ASBP-3 outlined above.

Rehabilitating infrastructure for water efficiency

As was described above, high water usage in Central Asia is often a consequence of deteriorated infrastructure and inefficient irrigation techniques. Therefore, many donors have invested in the rehabilitation of irrigation systems and the modernization of irrigation technologies. Agriculture is an important means of income and its upgrading can not only make a contribution toward more efficient water use but also toward improving rural livelihoods. Donors have also financed projects to modernize hydropower plants in order to increase their efficiency and output, as well as to build new ones. Nevertheless, all donors agree that technical improvement and more efficiency alone cannot solve the water problems in Central Asia. It can only be one component in an overall approach that needs comprehensive management and governance reforms at local, national and regional levels. Therefore, many donors combine technical assistance with support to institution-building. The World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, USAID, and many other donors and NGOs, for example, have been very active in establishing and supporting Water User Associations that are in charge of renovated channels at the local level.

Supporting local transboundary water management

Experience has shown that conflicts are more likely to emerge on the local level than on the interstate level. While the big transboundary rivers receive more attention, donors have also started to support the joint management of small transboundary rivers and canals in border regions. Since 2001, the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation SDC has been funding a programme on the introduction of the Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) principles in the Ferghana Valley. It is implemented by the Scientific Information Centre of ICWC, in cooperation with the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) in the Kyrgyz, Tajik and Uzbek parts of the valley. The objective is to reorganize the water management organizations within hydrographic boundaries, introduce public participation in decision making and improve water allocation mechanisms among the users. The programme also includes technical measures for saving water and increasing agricultural productivity, as well as automated operational systems along the canals, coupled with data transmission for improving water flow stability and water allocation transparency. In its pilot areas, the program was able to achieve up to 20% water saving – essentially with institutional reform and increased awareness of water officials and capacity of users.[See http://www.swiss-cooperation.admin.ch/centralasia/en/Home/Regional_Activities/Integrated_Water_ Resources_Management.]

Within the «Transboundary Water Management in Central Asia Program», the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) has one component that focuses especially on small transboundary rivers that are particularly suited to applying the basic principles of river basin management. In the Isfara and Khodzhabakirgan Basins shared by Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, the programme has been supporting both countries in joint transboundary river basin planning and management. A framework agreement on the establishment of a Joint Water Commission to coordinate and administrate these river basins has been drafted. Both countries collect, store and operate their data on these rivers in a compatible way.[See www.waterca.org.]

Improving data availability and exchange

One major obstacle for regional water cooperation is the lack of reliable data. This concerns, on the one hand, missing monitoring and measuring data due to the closure or lack of measurement points, especially in the areas of water formation. On the other hand, it refers to the absence of a region-wide accepted system of data exchange. Sharing data and planning are considered first steps in building up trust and initiating cooperation among riparian states, so many donors are active in this sphere.

Since 2003, the Central Asia Regional Water Information Base (CAREWIB), which is financed mainly by SDC and implemented by SIC ICWC, in cooperation with UNECE and GRID Arendal, has maintained an Internet portal with information and databases on water and the environment in Central Asia, including up-to-date flow data. The World Bank, in the framework of its regional «Central Asia Energy-Water Development Program» (CAEWDP), is supporting hydrometeorology services in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, as well as their regional coordination. One main component of the German «Berlin Process» is the regional research network «Central Asian Water» (CAWa), coordinated by the German Research Centre for Geosciences (GFZ) in close cooperation with the Central Asian Institute of Applied Geosciences (CAIAG) in Bishkek. Its objective is to contribute to a sound scientific and reliable regional data base for the development of sustainable water management strategies by, among other things, installing hydrometeorological stations and conducting analysis of the impacts of climate change.[See http://www.cawater-info.net, http://go.worldbank.org/OG3ADWOAK0, http://www.cawa-project.net/.]

Creating platforms for dialogue

The history of IFAS and other regional institutions has shown that mutual mistrust and lack of positive perceptions of benefits are a major obstacle to regional cooperation. Therefore, international actors also finance and organise regional conferences and meetings as platforms for political dialogue. Based on its 2007 Strategy for a New Partnership with Central Asia, the European Union has established an EU-Central Asia Platform on Environment and Water with regular high-level conferences as well as working group meetings for senior officials. The UN Regional Centre for Preventive Diplomacy in Central Asia (UNRCCA) regularly engages the political leadership in dialogue on water. The UNECE Water Convention brings together water experts from Central Asia and the Caucasus, including from countries not party to the convention. The World Bank, in conjunction with its involvement in the preparation of two assessment studies on the controversial Roghun hydropower plant in Tajikistan, facilitates a structured process for riparian involvement, including information exchange meetings with representatives of governments as well as civil society from all riparian states.[See http://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/where/asia/regional-cooperation-central-asia/index_en.htm,

http://unrcca.unmissions.org/, http://go.worldbank.org/ZQXIA8J0H0.]

These conferences and their joint statements often have no binding character and no concrete results. But one must not underestimate their contribution to regional confidence-building, reduction of mutual mistrust and acquainting Central Asia water experts with international principles and practices. In fact, cooperation failure is often not rooted in an unwillingness to cooperate or to share but in a reluctance to trust. From this point of view, it is of significant value that international players provide forums where high-level politicians as well as bureaucrats can meet and exchange views.

On 1 April 2008, the German Federal Foreign Office announced the launch of a water initiative for Central Asia at the Berlin water conference «Water Unites-New Perspectives for Cooperation and Security». The initiative was conceived as an integral component of the EU Strategy for a New Partnership with Central Asia, adopted in June 2007, during the German EU presidency. The Berlin Process, as it became known, presents an offer by the German Federal Government to the countries of Central Asia to support them in water management and to make water a subject of intensified transboundary cooperation. The primary goal is to set in motion a process of political rapprochement in Central Asia that leads to closer cooperation on the use of water resources and that may result in joint water and energy management in the long term.

The most extensive element of the Berlin Process is the Transboundary Water Management in Central Asia Programme, which the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH is carrying out on behalf of the German Federal Foreign Office. GIZ is collaborating closely to that end with national and international partners such as the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). Under that programme, measures have been implemented since 2009 that not only optimise cooperation in the Central Asian water sector, but also improve the lives of people in the region.

These were just some examples and not an exhaustive list of the wide range of activities and the deep engagement of donors. Their activities, when good coordination is in place, are not competing but rather complementary. Third parties can play a supportive role in fostering regional water cooperation when they are perceived as neutral. International players have supported cooperative actions and provided additional incentives and benefits to the riparian states. But though they can create enabling conditions for regional cooperation, the cooperation itself has to develop from within and depends upon the actions and will of the riparian countries.

Conclusion

Since they gained their independence 20 years ago, Central Asian states have undertaken tremendous efforts to cope with the environmental legacies of the past and to get prepared for the challenges of the future.

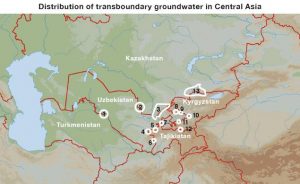

Although some successes have been achieved in building up regional cooperation and preventing conflicts about water, the southern Aral Sea is still dying and a sustainable mechanism for water use and distribution has not been found. Afghanistan is so far not included in the regional agreements. Furthermore, regional agreements and actions mainly address ad hoc the question of water distribution but not of water quality and reservoir working regimes. Monitoring systems exist neither for the water quality of transboundary rivers nor for transboundary aquifers. Finally, the water-energy nexus is neglected by the existing regional approaches or has failed when it has been tried.

Nevertheless, the Aral Sea Basin also provides an example of how shared water resources can stimulate a process of cooperation, even under difficult circumstances. Although the results of this cooperation are still not satisfactory, the institutions have served as a safety valve1 to prevent water conflicts. The presidents of the Central Asian countries have repeatedly stated their commitment to joint water management, as with the Almaty Declaration in 2009. International players have helped to build up the structure and space for cooperation and provided incentives. Strong and effective regional water institutions, especially IFAS, are an important pillar for regional stability.

Notwithstanding the challenges of the past and of the future, mutually beneficial cooperation on water and energy resources is possible in Central Asia. In fact, joint action is the only way to meet these challenges and turn them from obstacles into opportunities for sustainable development of the region as a whole.

The Way Forward

All over the world, countries that share waters strive to find adequate joint management mechanisms. In Central Asia, the disastrous consequences of the drying up of the Aral Sea, the impacts of climate change, the economic needs in times of transition and crisis, the challenge of building up regional cooperation simultaneously with internal state-building-all these factors pose an additional challenge to the management of transboundary water courses.

Being a vital resource for various economic sectors, sound water management has to account for all these interests and needs. As this has not been done sufficiently so far, regional agreements and organizations have lacked unanimous and long-term support from their members. The experience has shown that when agreements do not take the interests of all parties into account and are not perceived as fair by all parties, implementation and compliance soon cease and they fail to achieve their objectives.

Water is, in fact, a precious resource for the people and the states of the region. With this knowledge, further steps still need to be taken with regards to professional water-related planning, water saving and water productivity linked to food security. Contributions to the financing of water infrastructure and its rehabilitation by the international community increases the amount of water available and may contribute to buying time for further structural changes introduced to respective economic sectors by national policies. International players have been and continue to be willing to support Central Asian countries with these structural changes. As member countries of the UNECE, the Central Asian states can benefit from the tools and assistance provided under its environmental conventions, especially the Water Convention. It offers a framework of shared principles, a platform for dialogue and concrete capacity-building measures and assistance, while leaving room for specific agreements appropriate to the situation in the respective countries.

Cooperation on transboundary water resources yields a considerable peace dividend. It is up to the Central Asian states to realize the benefits of mutual cooperation in this field: stability and better socioeconomic development perspectives, as opposed to the high costs of fully self-reliant policies and security risks attached to a lack of cooperation. But in order to realise these benefits, transparency and equal participation in regional decision-making is necessary so that all interests and needs are taken into account. A regional organization like IFAS can provide the appropriate platform to support such a process. Structural deficits so far have prevented IFAS from living up to its potential. The reform process initiated with the statements of the heads of states in 2009 has opened a historic window of opportunity to revive regional cooperation and put its foundation on a more robust basis. It will be a long and challenging path to overcome old patterns of regional mistrust. Donors have been supporting this and there is a great need for them to continue doing so. Nevertheless, while international actors can foster cooperation by «paving the way», it is the Central Asian players that will have to walk the walk.

Infoboxes:

Climate change affects water

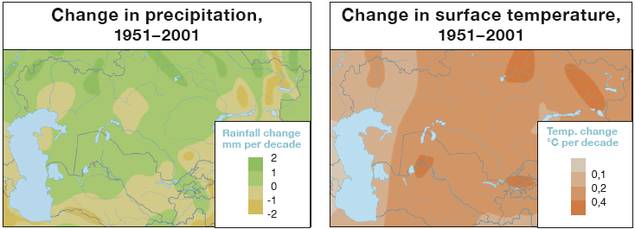

Central Asia is characterised by an arid and continental climate. This means that summers are very hot (up to 50°C in the deserts), winters are very cold (down to -60°C in the high mountain areas of the Pamirs in Eastern Tajikistan) and precipitation is very low. Over the last few decades, global warming has led to an increase in the surface temperature in Central Asia. The map below shows that increase per decade.